In the Arabic Version, Rabbeinu Avraham always quotes his sources in full. In the Hebrew, by contrast, these references are generally shortened, sometimes by tens or hundreds of words. This makes sense if the translator’s goal was not to preserve a faithful copy of the “Ma’amar” [Discourse] for posterity... -- Rabbi Moshe Meiselman TCS pg. 99

The Accuracy of the Translation

The full Hebrew version of Discourse that we have today is a translation from the original Arabic. Is there any way for us to verify that the translation was competent or accurate? Happily, the answer is "yes". While it is not possible to validate the entire translation, an Arabic version exists for approximately one third of the Discourse. Rabbi Meiselman stipulates that "[a] comparison of the published text with the surviving Arabic segment reveals that the translation is generally competent." (TCS pg 97). [1]

Nevertheless, Rabbi Meiselman raises a number of issues with the translation which he believes places doubt in its accuracy:

- There are a number of places where the Hebrew translation differs from the Arabic including one case where the meaning of the text is completely reversed.

- The translator has “used poetic license to spice up the text”.

- The translator has added words to either clarify the text or for “innocent embellishment”

- The translator in one case includes a translation which “bears no relation to the extant Arabic version at all”.

We'll base our analysis on a side by side comparison of the Hebrew translation of the Discourse and the new Hebrew translation from the surviving Arabic fragments which can be found in the Appendix of TCS.

Let’s start by looking at the one case where the meaning of the text has purportedly been reversed. Obviously, if the translator gets things backwards, this could indicate a serious deficiency.

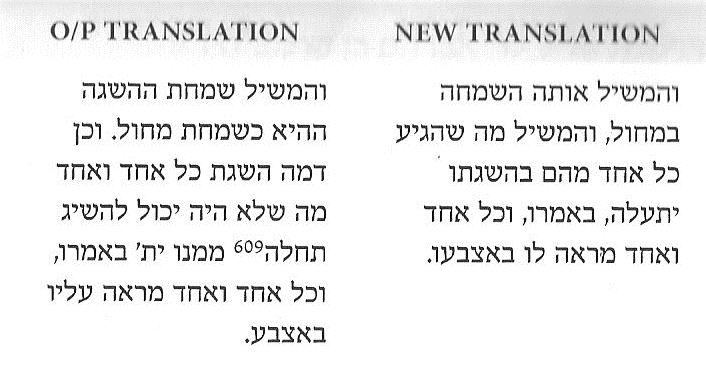

(The text on the left is the Discourse in Hebrew. The text on the right a new translation of the Arabic version.)

This bit of the Discourse discusses the following Midrash (Taanis 31a):

The “old” translation of the Discourse has the following (the bold section of the translation is where the Rabbi Meiselman claims that the meaning has been reversed):

This bit of the Discourse discusses the following Midrash (Taanis 31a):

In the future, the Holy One, praised be He, will take a dance for the righteous in the garden of Eden placing Himself in the center, and everyone will point at Him with his finger and say, (Is. 25, 9) 'Behold, this is our God; we have waited for him; we will be glad and rejoice in His salvation.’ (Soncino Translation)Rabbeinu Avraham unsurprisingly rejects the plain meaning of the Midrash as a gross anthropomorphism. The phrase "in the future" indicates that the Midrash is actually describing an element of the non-physical world to come. Souls in the world to come, now detached from the corrupting influence of their physical bodies, can come to a higher understanding of God than they could while attached to a body in this world. The happiness of a dance is an allegory for the happiness that the soul experiences at its new deeper understanding of God, represented by the pointing of the finger.

The “old” translation of the Discourse has the following (the bold section of the translation is where the Rabbi Meiselman claims that the meaning has been reversed):

The reward for the righteous who are remembered for life in the world to come, is an understanding of God, the elevated one, that they were not able to understand in this world in any manner. This is the ultimate good such that there is none higher than it. And he allegorized this happiness of this understanding as the happiness of a dance. And he also compared the understanding of each individual, that which he was not able to understand initially [while in this world], [with the allegory] "and each and every one gestures towards Him with a finger.”The new translation has it this way:

The reward for the righteous who are remembered for life in the world to come is their understanding of Him, the elevelated One, what was impossible for them to understand in this world. This is the ultimate reward and the pinnacle of happiness, and he allegorized it to the happiness of a dance. And he allegorized what each of them reached in understanding of Him, the elevated One, in saying, each and every one of them gestures at Him with his finger.

The meaning is precisely the same! One text says that the soul reaches a new level of comprehension, while the other says that it has a level of comprehension which it was not able to achieve before. It appears that the translator has correctly clarified the meaning of “the understanding of each individual” as the new understanding achieved in the world to come compared to that which was achieved previously in this world.

Here is another section that Rabbi Meiselman takes issue with. Rabbeinu Avraham continues in his explanation of the Midrash. In the Midrash, the participants in the dance recite a Pasuk which refers to God's salvation. This indicates the fact that the soul survives the destruction of the body in death.

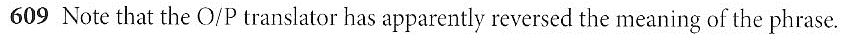

Rabbi Meiselman claims that the translation has been "spiced up" and embellished, and new text has been interpolated. Let's investigate:

The old translation:

Next, Rabbi Meiselman characterizes the use of the phrase “the wrath and the fury” in place of the “true destruction” as an attempt by the translator to use “poetic license to spice up” the text. He also characterizes the words “with God’s help” as an “innocent embellishment”. However, the intent of the translator with both of these seems clear. It is traditional to substitute a euphemism or otherwise avoid direct reference to very negative occurrences and to soften them. The words “the wrath and the fury” were not chosen at random. They are a reference to the same words in Deuteronomy 9:19, where they mean precisely destruction.

[Edit: Commenter "Magiha" points out an alternate explanation here: the Roshei Teivos (abbreviation) for "with God's help" and "the world to come" ("B'Ezras Hashem"/"B'Olam Haba") are identical. Thus, the Hebrew translator could have used the abbreviation, which was then expanded incorrectly by a later copyist].

The old translation:

And he brought a proof of the escape of the intellective soul from the wrath and the fury, with God’s help, in that which the pasuk says “and he will save us”.The new translation:

And he brought proof of the privilege and the escape from the true destruction in the next world in that which the pasuk says “and he will save us”.Rabbi Meiselman’s first criticism of this translation is the addition of the words “intellective soul” in the translation. In my humble opinion, the intent of the translator was clear. He understood that Rabbeinu Avraham did not believe that one lives on intact as a physical being in the world to come; rather the body is destroyed while the intellective soul lives on. (See Mishneh Torah, Yesodei Hatorah 4:14-16 where the Rambam make this explicit). Thus the “added” words do not alter the meaning in any way, but simply serve to clarify.

Next, Rabbi Meiselman characterizes the use of the phrase “the wrath and the fury” in place of the “true destruction” as an attempt by the translator to use “poetic license to spice up” the text. He also characterizes the words “with God’s help” as an “innocent embellishment”. However, the intent of the translator with both of these seems clear. It is traditional to substitute a euphemism or otherwise avoid direct reference to very negative occurrences and to soften them. The words “the wrath and the fury” were not chosen at random. They are a reference to the same words in Deuteronomy 9:19, where they mean precisely destruction.

כִּי יָגֹרְתִּי, מִפְּנֵי הָאַף וְהַחֵמָה, אֲשֶׁר קָצַף יְהוָה עֲלֵיכֶם, לְהַשְׁמִיד אֶתְכֶם

For I was in dread of the anger and hot displeasure [the wrath and the fury], wherewith the LORD was wroth against you to destroy you.The addition of the words “with God’s help” is not an embellishment, but a expression of hope that we are not afflicted with such a punishment.

[Edit: Commenter "Magiha" points out an alternate explanation here: the Roshei Teivos (abbreviation) for "with God's help" and "the world to come" ("B'Ezras Hashem"/"B'Olam Haba") are identical. Thus, the Hebrew translator could have used the abbreviation, which was then expanded incorrectly by a later copyist].

In the end, I believe these three criticisms are misplaced because they evaluate the translation by the standards one would apply to a modern scholarly one. In a modern translation, the words “intellective soul” would be surrounded by square brackets to make clear that the words are added to aid the reader. The medieval texts have very little in the way of punctuation, and such a convention was neither yet invented nor available to the translator. The other two “changes” in the paragraph reflect the fact that the translator approached the translation as a religious act rather than as a detached scholarly effort. The bottom line is the translation here is completely accurate; what Rabbi Meiselman proves is that the translation is not modern.

Let's examine Rabbi Meiselman's example “where the translation bears no relation the extant Arabic at all”. (TCS pg. 98). The context is Rabbeinu Avraham’s explanation of the following Aggadah (Berachos 5a)

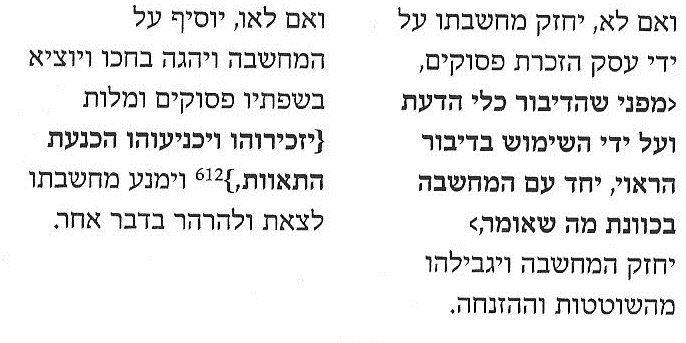

Here is the old translation on the right and the new one on the left:

The old translation explains that the aggadah is providing advice on the method to subjugate his passions and desires to his intellect. The advice to “let him study the Torah” works as follows: one should both concentrate on and enunciate pesukim that involve the subjugation of human desires.

Rabbi Meiselman points out that the new translation merely mentions that the recitation of pesukim helps because speech is the “vessel” of thought and so reinforces proper thought, but says nothing about specifically mentioning pesukim that involve the subjugation human desires. Did the translator make that part up and insert a “translation [that] bears no relation the extant Arabic at all”?

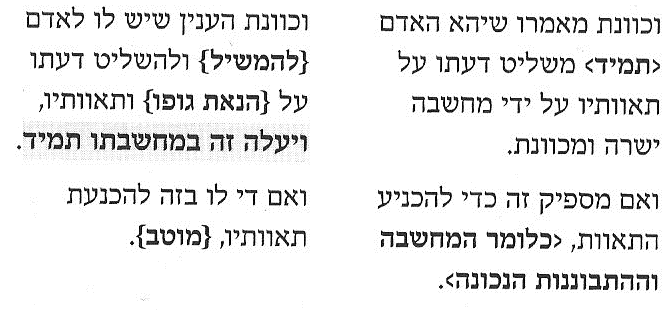

It is easy to see that the answer to this question is “no”, if you read the passage in context. Here is the preceding paragraph:

Here, Rabbeinu Avraham explains that the first step is to subjugate human desire through proper thought. Then, if this is not sufficient, the advice is to recite pesukim, since speech reinforces thought. The translator interpreted this to mean that the topic of the pesukim themselves would the subjugation of human passion.

Moreover, the translator didn’t invent this idea. Rabbeinu Avraham himself supplies this explanation in the following paragraphs:

Here, Rabbeinu Avraham explains why reciting Shema is the next piece of advice that the Gemara has. He says here explicitly that one of the reasons for this advice is that the Shema includes the subjugation of the passions in the commandment “do not stray after your heart and after your eyes”. The translator applies Rabbeinu Avraham's explanation for reciting Shema as the reason for recitation of other pesukim.

We have shown untrue that "the translation bears no relation the extant Arabic at all". But why did the translator introduce Rabbeinu Avraham's explanation one paragraph early if it was not in the original text?

The answer is clear if you compare the text of the Midrash as quoted in the Hebrew version and Arabic versions as we see here:

The Hebrew version omits the clause “If not, let him study the Torah. For it is written: 'Commune with your own heart'. If he subdues it, well and good.” As a result, it is likely the translator considered Rabbeinu Avraham’s discussion of the recitation of pesukim as part of his discussion of the recitation of Shema. Thus is further reinforced by the following:

The Hebrew translation omits the segue “If this is enough, otherwise…” between the discussion of the recitation of pesukim from the recitation of the Shema. The translator understood Rabbeinu Avraham's discussion of pesukim and Shema to be a single unit since his version of the Midrash did not have an independent clause referring to the recitation of pesukim. As a result, there was no transposition at all in the translation.

Besides the accuracy of the translation, Rabbi Meiselman notes two aspects of the Discourse which indicate “translator’s goal was not to preserve a faithful copy of the Ma’amar for posterity, but to draw support from it for his own thesis.”

In my humble opinion, discerning the intent of the translator is close to irrelevant for our purposes. We have direct access to the Arabic versions of portions of the Discourse, we can judged directly for ourselves the competence of the translator. Since the translation is accurate for the significant fraction of the Arabic text that we have, we can have confidence in the translation. Nevertheless, we'll address the evidence that Rabbi Meiselman brings and show that they do not bear any relevance to the issue.

His first piece of evidence for this is the fact that the translation of the Discourse is introduced by the following introduction (Rabbi Meiselman’s translation TCS pg 91):

To begin with, if it is true that the translator intended the translation be incorporated into a larger work (and this may not be the case), it would not indicate that the translation is somehow deficient. Rabbi Meiselman includes the Discourse in his own work in order to support his thesis, but it is for this very reason that he treats the Discourse with painstaking care.

Next, Rabbi Meiselman then notes that the sources quoted in the Arabic are abridged in the Hebrew version, sometimes by hundreds of words. He states that “[t]his makes perfect sense if the translator’s goal was not to preserve a faithful copy of the Ma’amar for posterity, but to draw support for it from his own thesis”. In my humble opinion, this is a complete non sequitur.

To begin with, all of the shortened references are in Hebrew and not in Arabic. The inclusion of the full text of these references would not serve to preserve the Arabic for the Hebrew reader in any way. They would be simply an exercise in tedious copying while adding nothing to the store of the world’s knowledge.

Secondly, in the age before the printing press, it is not at all clear that making the translation longer would serve to “preserve a faithful copy of the Ma’amar”. The shorter the work, the more likely it could be copied further and spread to a wider audience.

Thirdly, it is quite traditional to abridge sources in religious works. The Talmud itself abridges pesukim all the time with the assumption that the reader knows what is being referred to. The Vilna Gaon's commentary on the Shulchan Aruch often consists of a string of references to the Talmud or Rishonim with no other explanation. In the religious context, the translator would then have no reason not to abridge sources to save costs as well as to make his translation more compact and easier to copy.

Finally, as Rabbi Meiselman notes, the different manuscripts abridge the sources differently. Thus, it is not even clear that it was the translator who did the abridgment. (Ironically, Rabbi Meiselman himself reports in the preface of TCS (pg. xxii) that he was forced by his publisher to abridge sources in order to make the length of his book practical).

At this point, we've shown that there is no evidence to question the reliability of the Hebrew translation of the Discourse. We'll now turn to placing the Discourse into a modern context.

Comments are both welcome and encouraged. I'll make every effort to address any questions or arguments posted in the comments.

Let's examine Rabbi Meiselman's example “where the translation bears no relation the extant Arabic at all”. (TCS pg. 98). The context is Rabbeinu Avraham’s explanation of the following Aggadah (Berachos 5a)

R. Levi b. Hama says in the name of R. Simeon b. Lakish: A man should always incite the good impulse [in his soul] to fight against the evil impulse. For it is written: Tremble and sin not. If he subdues it, well and good. If not, let him study the Torah. For it is written: 'Commune with your own heart'. If he subdues it, well and good. If not, let him recite the Shema'. For it is written: 'Upon your bed'. If he subdues it, well and good. If not, let him remind himself of the day of death. For it is written: 'And be still, Selah'.

Here is the old translation on the right and the new one on the left:

The old translation explains that the aggadah is providing advice on the method to subjugate his passions and desires to his intellect. The advice to “let him study the Torah” works as follows: one should both concentrate on and enunciate pesukim that involve the subjugation of human desires.

Rabbi Meiselman points out that the new translation merely mentions that the recitation of pesukim helps because speech is the “vessel” of thought and so reinforces proper thought, but says nothing about specifically mentioning pesukim that involve the subjugation human desires. Did the translator make that part up and insert a “translation [that] bears no relation the extant Arabic at all”?

It is easy to see that the answer to this question is “no”, if you read the passage in context. Here is the preceding paragraph:

Here, Rabbeinu Avraham explains that the first step is to subjugate human desire through proper thought. Then, if this is not sufficient, the advice is to recite pesukim, since speech reinforces thought. The translator interpreted this to mean that the topic of the pesukim themselves would the subjugation of human passion.

Moreover, the translator didn’t invent this idea. Rabbeinu Avraham himself supplies this explanation in the following paragraphs:

Here, Rabbeinu Avraham explains why reciting Shema is the next piece of advice that the Gemara has. He says here explicitly that one of the reasons for this advice is that the Shema includes the subjugation of the passions in the commandment “do not stray after your heart and after your eyes”. The translator applies Rabbeinu Avraham's explanation for reciting Shema as the reason for recitation of other pesukim.

We have shown untrue that "the translation bears no relation the extant Arabic at all". But why did the translator introduce Rabbeinu Avraham's explanation one paragraph early if it was not in the original text?

The answer is clear if you compare the text of the Midrash as quoted in the Hebrew version and Arabic versions as we see here:

The Hebrew version omits the clause “If not, let him study the Torah. For it is written: 'Commune with your own heart'. If he subdues it, well and good.” As a result, it is likely the translator considered Rabbeinu Avraham’s discussion of the recitation of pesukim as part of his discussion of the recitation of Shema. Thus is further reinforced by the following:

The Hebrew translation omits the segue “If this is enough, otherwise…” between the discussion of the recitation of pesukim from the recitation of the Shema. The translator understood Rabbeinu Avraham's discussion of pesukim and Shema to be a single unit since his version of the Midrash did not have an independent clause referring to the recitation of pesukim. As a result, there was no transposition at all in the translation.

The Purpose of the Translation

Besides the accuracy of the translation, Rabbi Meiselman notes two aspects of the Discourse which indicate “translator’s goal was not to preserve a faithful copy of the Ma’amar for posterity, but to draw support from it for his own thesis.”

In my humble opinion, discerning the intent of the translator is close to irrelevant for our purposes. We have direct access to the Arabic versions of portions of the Discourse, we can judged directly for ourselves the competence of the translator. Since the translation is accurate for the significant fraction of the Arabic text that we have, we can have confidence in the translation. Nevertheless, we'll address the evidence that Rabbi Meiselman brings and show that they do not bear any relevance to the issue.

His first piece of evidence for this is the fact that the translation of the Discourse is introduced by the following introduction (Rabbi Meiselman’s translation TCS pg 91):

I have found written by HaRav Rabbeinu Avraham Ben HaRav Rabbeinu Moshe ztz”l is a sefer he composed in the Arabic language called al-Kafiyah, the following words which contain great benefit for my needs, and translating them from his language into the Holy Tongue is fitting for me and proper.In the one manuscript of the Discourse, there is an even longer prologue which contains a possible reference to a larger work by the prologue’s author: “And this principle and its ramifications will be explained thoroughly in the second chapter”. (As Rabbi Meiselman notes, this prologue may not have been written by the translator as it is omitted from a different manuscript).

To begin with, if it is true that the translator intended the translation be incorporated into a larger work (and this may not be the case), it would not indicate that the translation is somehow deficient. Rabbi Meiselman includes the Discourse in his own work in order to support his thesis, but it is for this very reason that he treats the Discourse with painstaking care.

Next, Rabbi Meiselman then notes that the sources quoted in the Arabic are abridged in the Hebrew version, sometimes by hundreds of words. He states that “[t]his makes perfect sense if the translator’s goal was not to preserve a faithful copy of the Ma’amar for posterity, but to draw support for it from his own thesis”. In my humble opinion, this is a complete non sequitur.

To begin with, all of the shortened references are in Hebrew and not in Arabic. The inclusion of the full text of these references would not serve to preserve the Arabic for the Hebrew reader in any way. They would be simply an exercise in tedious copying while adding nothing to the store of the world’s knowledge.

Secondly, in the age before the printing press, it is not at all clear that making the translation longer would serve to “preserve a faithful copy of the Ma’amar”. The shorter the work, the more likely it could be copied further and spread to a wider audience.

Thirdly, it is quite traditional to abridge sources in religious works. The Talmud itself abridges pesukim all the time with the assumption that the reader knows what is being referred to. The Vilna Gaon's commentary on the Shulchan Aruch often consists of a string of references to the Talmud or Rishonim with no other explanation. In the religious context, the translator would then have no reason not to abridge sources to save costs as well as to make his translation more compact and easier to copy.

Finally, as Rabbi Meiselman notes, the different manuscripts abridge the sources differently. Thus, it is not even clear that it was the translator who did the abridgment. (Ironically, Rabbi Meiselman himself reports in the preface of TCS (pg. xxii) that he was forced by his publisher to abridge sources in order to make the length of his book practical).

At this point, we've shown that there is no evidence to question the reliability of the Hebrew translation of the Discourse. We'll now turn to placing the Discourse into a modern context.

Comments are both welcome and encouraged. I'll make every effort to address any questions or arguments posted in the comments.

Notes

[1] The full text of the Discourse that we have today is known to us only in Hebrew translation. The Discourse was first published in 1836 in the journal Keren Chemed and eventually included in 1887 Vilna edition of Ein Yaakov based on a manuscript currently housed in the Oxford Bodleian Library (TCS pg. 94). Two other manuscripts also exist, one of which is unreliable as it contains obvious changes, as well as an attempt by its “author” Eliezer Eilburg to attribute part of the Discourse to himself. (TCS pg. 95). However, it is clear that this manuscript was derived from the Oxford manuscript so we can rule out the possibility that Eilburg had inserted the section which references Chazal’s scientific statements. (TCS pg 95 note 264).

In addition to the Hebrew translations, a version of the Discourse in Arabic (approximately the middle third) was found in the Cairo Geniza. In the appendices of TCS, Rabbi Meiselman has published a version of the Hebrew text which utilizes all three manuscripts as well the publication of Discourse in Kovetz Teshuvos HaRambam. TCS also includes a publication of the Arabic text, along with a new translation by Rabbi Yaakov Wincelberg with editing by Rabbi Pinchas Korach and with a comparison to the Hebrew Translation.

Finally, Rabbi Meiselman also publishes a Synopsis of the Discourse by Rav Vidal HaTzorfati (1540-1619) which mentions the 5 categories of Derashot and 4 categories of stories, but not the section of the discourse which discussed Chazal’s statements on science.

It's kind of telling that R' Meiselman can't bring himself to simply say, "Well, R' Avraham was wrong." Great as he was, it's not like he has the stature of his father. This is, of course, a common affliction of those who believe in "da'as torah;" since they can't argue with a "gadol," they make up elaborate conspiracy theories about mistakes, translations, and forgeries.

ReplyDeleteI first noted this in connected with R' Meiselman years ago, when he wrote a piece in Tradition arguing that R' Soloveitchik was not a Zionist (!). Again, "da'as torah" does not mean "I do whatever the gedolim do" so much as "I do what I want and rewrite the gedolim to match."

It's kind of telling that R' Meiselman can't bring himself to simply say, "Well, R' Avraham was wrong." Great as he was, it's not like he has the stature of his father.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment.

1) I think that point the of the book is to show that the viewpoint espoused in the Discourse is illegitimate and obviously so. It is hard to say that about Rabbeinu Avraham.

2) The Rambam makes similar statements, as I hope that I have shown. And Rabbeinu Avraham refers back to his father's statements. So if Discourse if valid, then it provides further evidence that the Rambam agreed (although I think that is obvious on its own).

3) Rabbi Meiselman does seem to imply that Rabbeinu Avraham is not in the first rank of authorities. On page 87-88, he writes "While he was alive and for some time afterwards these writings were influential. Nevertheless, they never achieved the level of acclaim and acceptance that would have granted them a permanent place on Jewish bookshelves." Footnote says: "It is beyond the purview of this book to explore the reasons for this, but the fact is that his works did not achieve such a place".

Personally, I think that this logic is somewhat suspect. The fact that he wrote in Judeo-Arabic probably had as a large an impact as his greatness did.

I first noted this in connected with R' Meiselman years ago, when he wrote a piece in Tradition arguing that R' Soloveitchik was not a Zionist (!). Again, "da'as torah" does not mean "I do whatever the gedolim do" so much as "I do what I want and rewrite the gedolim to match."

On that, please see Kaplan, Lawrence. Revisionism and the Rav: The Struggle for the Soul of Modern Orthodoxy if you haven't already.

David: The first example you cite is devastating. I have been wracking my brains trying to figure out how in the world R..Meiselman could so misunderstand the old translation so as to claim that it reverses the meaning of the text, and still can't do so.

ReplyDeleteLawrence Kaplan

Interesting. I never paused to consider the issue. I suppose that we're all subject to unconscious bias in supporting our respective theses.

DeleteI just pulled down my dusty copy of TCS to reread the chapter on Rav Avraham Ben HaRambam. I make no claim of being an impartial expert, but I was again struck by the feeling that Rav Meiselman attempts to bore and bamboozle the reader into submission. After 12 pages of copiously footnoted blather, I gave up, angry and frustrated. It feels like pseudo-scholarship, and I'm glad that there are people like R Ohsie who have the resources and patience to subject his writings to scholarly criticism.

ReplyDeleteAnd well done for keeping the argument civil!

I suppose that it's easier to have patience if you know that you have a chance publish something on the topic. Self-interest trumps boredom :).

Deletehave you shown or intend to show your article to rabbi Meiselman?

ReplyDeleteI think that trying to do so would be disrespectful. I'm discussing ideas not authors. He has at least one close student who reads this blog and who can bring any relevant points to his attention if he feels that would be beneficial.

DeleteYes, I wonder whether the blog "Slifkin Challenge," run by David Kornreich, R. Meiselman's student, will respond to these posts.

DeleteLawrence Kaplan

One could safely assume that the "B'Ezras Hashem" / "B'Olam Haba" switch, is actually based on the Roshei Teivos having been mixed up at some point: BaisAyin"Heh works for either.

ReplyDeleteIf this thesis is correct, the original Hebrew translator actually wrote BaisAyin"Heh and a later copyist expanded it to "B'Ezras HaShem", not realizing it should have been "B'Olam HaBa"

Excellent point. I'm going to steal it and put it into the body of the post.

DeleteHi David,

ReplyDeleteThank you for these fascinating posts.

Although you understandably do not like ad hominem arguments, while your arguments are sound, well constructed and persuasive, (if not irrefutable). I think that you have missed the purpose of Rav Meiselman's book.

The fact is that the person who wants to agree with Rav Meiselman's thesis, reading the book is irrelevant. These people will use an argument of authority to maintain their belief in Da'at Torah and the issur in believing in evolution. The argument itself is irrelevant, all they need to say is , "Rav Meiselman, PhD for mathematics, nephew of Rav Solevitchik has shown...." The intended market for the book needs the book, not its contents.

Rav Meiselman's book is also not intended for this generation. Rather, by writing this book, with approbation I presume, he has established a "tradition" of viewing the standard translation of Discourse suspect, at least in the English speaking world. It takes only 2 seconds to tell a lie, it will take 100 years to prove it was a lie. Although essays like the ones posted here refute Rav Meisleman's thesis, the fact that his book was published at all means that this is a lie that will need to be argued every generation.

But don't let my cynicism detract from the fact that these are brilliant, informative and valuable essays.

Yossi

Yossi, thank you for the thought-provoking comment. Two responses that come to mind quickly:

Delete1) The one thing that's most difficult to predict is the future. So you may very well be correct, but it's best to hedge one's bets.

2) You may be right about the target audience for Rabbi Meiselman's book. But I believe that there is another class of people, who in fact understand that the various aspects of modern science are irrefutable, but who are not sure what the attitude of Orthodox Judaism is. They may identify Orthodox Judaism with its right wing, and be turned off by the notion that have to make a choice between two contradictory approaches. For this reason, I think there is value in showing that even the most "right wing" or seemingly "reactionary" versions of Judaism actually have a tradition of openness in understanding science and are not universally fundamentalist in approach. Maybe I'm making a dent there.

3) You'd be surprised how many "closet" philosophers are hanging out in the most right wing of places :). The approach is hidden plain sight to anyone who enters a Bais Midrash with a well stocked library.

If not, I have an admittedly base motive to simply gather eyeballs for my (sincere) prose. Perhaps I can at least accomplish that.

David, to whom are you referring with the term "right wing" and "reactionary" in connection with a non-fundamentalist approach to torah and science issues? I don't consider you "right wing", much less "reactionary". Nor is the Meiselman approach anything other than "reactionary" and "fundamentalist". I have yet to read one item of interest excerpted from the book, "Torah, Chazal, and Science", and I certainly don't intend to support his stance by buying it.

ReplyDeleteY. Aharon

Y. Aharon: What I was trying to say is that people who are "right wing" and therefore perceived as reactionary may actually endorse the notion of the importance of science and recognize scientific progress. See, for example, the latest post where the Chazon Ish, who is certainly "right wing" endorses the notion of scientific progress. And he is known to have studied secular sources.

DeleteHello David. I've been waiting for this website to respond to R Mesielman's argument since I first read it last year and finally this has been the response.

ReplyDeleteBut instead of focusing on the small points you should have addressed the bigger questions. It doesn't matter if you think the translator was faithful to the work while R Meiselman believes it was "spiced up and embellished". That is subject to your opinions.

The real question is why did Rav haTorzfati not have the part of the discussion on the science of Chazal. This point is our main concern and did not address it. Does it mean this section was added on since it was not in the original Arabic or original translations?

Please help clarify these issues for me.

Hello David. I've been waiting for this website to respond to R Mesielman's argument since I first read it last year and finally this has been the response.

ReplyDeleteThere have been others; e.g. see torahmusings.com.

But instead of focusing on the small points you should have addressed the bigger questions. It doesn't matter if you think the translator was faithful to the work while R Meiselman believes it was "spiced up and embellished". That is subject to your opinions.

I think that the claim of gross mistakes in the translation is more significant, but to each his own.

TCS has a whole list of arguments on this topic. It is a whole chapter. I take it as a compliment that you believe that believe that arguments that I did not address are the most significant, since that indicates that you feel that my objections have some substance.

Be that as it may, while I'll try to mention that argument somewhere along the line.

The real question is why did Rav haTorzfati not have the part of the discussion on the science of Chazal. This point is our main concern and did not address it. Does it mean this section was added on since it was not in the original Arabic or original translations?

In a word, no. Someone summarizing one part of another's writing doesn't mean that the unsummarized part is a forgery. I'll try to be more expansive in a post, God willing.

While I am not trying to say it's foolproof (that when one doesn't summarize fully it must mean it's a forgery) it is very substantial evidence and at least an alternate suggestion should be provided, because as it is, it is the most working theory.

ReplyDeleteWhen one summarizes that's exactly what it means- addressing all the major points in short. How could he have missed 1/4 of the essay which makes a major point that changes the perspective of Chazal and science which has been so heavily debated throughout history and especially in modern day. I am looking forward to your future posts. I really enjoy them. Beshem Hashem Na'se Ve'nasliach.

I don't see why it is evidence at all. I don't know what he had in front of him, I don't know what his purpose was, and I don't know what his thoughts were on the science aspects of the Discourse. This fact that someone "should have written" something else is just a conjecture at best.

DeleteThank you for the kinds words. Keep on reading...

Thanks for sharing the info,Certified translation agency keep up the good work going.... I really enjoyed exploring your site. good resource...

ReplyDeleteIn translation Accuracy is one of the biggest matter. Because it need more accuracy.

ReplyDelete